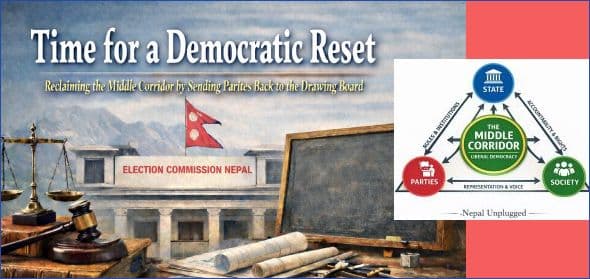

Time for a Democratic Reset: Why the Election Commission Must Act Now —Restoring Democratic Guardrails in Nepal’s Missing Middle Corridor

Anchoring the Middle Corridor by Sending Parties Back to the Drawing Board

Dr. Alok K. Bohara

Prelude

Nepal’s democratic journey has been shaped by lived extremes—centralized one-party rule on one end, and recurring fears of fragmentation and instability on the other. Since 1990, the challenge has never been merely to hold elections, but to keep democracy anchored in the middle, where authority is exercised with restraint and public voice is meaningfully reflected and represented through political parties. This balance depends on institutions—designed by public representatives, including political parties—but governed by rules that bind everyone equally: the state, the parties, and society itself. When these rules are respected, a stable state emerges that serves citizens fairly. This essay follows an earlier diagnosis of the Election Commission’s institutional failure and asks a harder question: how its long-standing abdication of gatekeeping allowed party machinery to overpower and take over key aspects of the state, its institutions, and society—blurring the line between state and society—and pushing Nepal away from its democratic middle corridor.

As Nepal watches a major political party fracture in real time, it is tempting to read the moment purely through the lens of personalities, factions, or immediate outcomes. But what is unfolding is better understood as a symptom of a deeper institutional failure—one that has been building quietly for years.

A Word on the Middle Path

Democracy does not survive on harmony. It survives on a managed tension between the state and society. It may sound contradictory, but this is what a healthy democracy is about: public representatives make the rules, while society retains the space to challenge and adjust them over time. Political parties play an intermediary role in this process—carrying public voice into the state, shaping reforms and refinements, and helping design institutions that are meant to serve everyone fairly, including the parties themselves.

The state seeks order, authority, and stability. Society seeks voice, rights, and accountability. When this tension is held in balance, democracy stays on its middle path. When it is not, systems slide toward extremes. Parties are meant to fine-tune this tension—between the state and society, and sometimes even between society and the parties themselves—without collapsing the distinction between them.

Institutions exist precisely to manage these tensions. When they function properly, they act as guardrails—preventing the state from becoming despotic, and preventing society from fragmenting into disorder or mob rule. Democracy lives in this narrow space between the two.

Nepal understands both extremes from lived experience.

Before 1990, we experienced one end of the spectrum: a centralized, one-party monarchical system where power was tightly controlled and political competition suppressed. On the other end, we have repeatedly faced fears of fragmentation—periodic calls for regional or ethnic separation whenever the center appears weak, unresponsive, or captured. Even today, many quietly fear that prolonged chaos could invite either an unruly strong executive or, in the worst case, a military “solution,” or even something worse.

These are not abstract fears. They are memories shaped by our own history.

When the state becomes too powerful, democracy drifts toward despotism. When society becomes fragmented and unruly, the state responds with coercion and force. In both cases, liberties shrink, economies suffer, and instability becomes the norm. Around the world, such imbalances have led to military coups, authoritarian regimes, economic collapse, refugee crises, and civil wars.

Political economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson describe this constant balancing act between the state and society as the Red Queen dynamic. Stripped of academic language, the idea is simple: democracy survives not by eliminating tension, but by containing it through capable and impartial institutions. When those institutions retreat or are captured, the balance breaks and the system spins out of control.

So where does Nepal stand today?

Ironically, Nepal’s political parties have transgressed into the state mechanism itself. Instead of remaining agents of change on behalf of the people, they have placed themselves above institutions by capturing state machinery and using it to serve party members and benefactors. In doing so, the distinction between the state and political parties has blurred.

The uncomfortable truth is that this balance has been slipping for years. Parties and the state gradually became one and the same, leaving the public without an effective counterweight. This slow capture of the state apparatus was enabled by the Election Commission’s failure to enforce its constitutional duty—to rein parties back within the democratic fold and preserve the middle path.

A Voice from the Ground

“In the country’s current unstable political environment, ordinary citizens are confused. When they go to vote, what should they give importance to—the party, the party’s ideology, the personality of the party chair, the person named as the future prime minister, or the party’s senior leaders?

In nation-building, the prime minister plays the most important role. Therefore, who becomes prime minister after the election is a serious matter. For development, leadership capacity is essential—clarity of direction, the courage to reform, the ability to decide in uncertainty, and moral authority.

Today, many individuals aspiring to become prime minister—from both old and new parties—are openly discussed in the media. If any impartial body or institution examined whether they actually possess these qualities, it would make it easier for voters to decide.”

This confusion is not a failure of voters, but a symptom of an electoral system that no longer provides clear institutional guidance.

How the Balance Was Hijacked

Nepal’s problem today is not a classic state-versus-society struggle, as it was during the pre-1990 democratic movement against monarchical rule. This is not society resisting an authoritarian state.

Instead, it is political parties exploiting constitutional loopholes to capture the state and its institutions—leaving society without impartial protectors such as the Election Commission, the judiciary, law enforcement, or anti-graft bodies.

Nepal’s parties went further. They seeded conflict across society by building dense cadre networks at the bottom while concentrating loyalty and privilege at the top. From water committees to school boards, forest user groups to colleges, nursing, journalism, and the bureaucracy—everything became fragmented along party lines. Society was no longer plural; it was partitioned.

The party modus operandi was simple: divide citizens so that no unified, credible pushback could emerge from below. We all recognize the symptoms—musical-chair prime ministerships, a proliferation of scandals, and, increasingly, the steady exodus of young people.

This strategy worked—until it didn’t.

From Institutional Drift to Open Breakdown

That long-simmering institutional failure is no longer abstract; it is now playing out openly within the political parties themselves.

The current turmoil within parties only reinforces why the Election Commission’s inaction over the years has mattered so deeply. The Nepali Congress’s internal party convention is now in deep disarray. The established faction wants to defer it until after the election, while a new crop of leaders—citing their party constitution and legally acquired signatures—is demanding a convention before the election, with fresh leadership and a renewed mandate. The two factions are imploding in full public view.

This is precisely where the constitution assigns an obligation to impartial arbiters to intervene, especially when such provisions are clearly spelled out in the Election Commission’s mandate.

Likewise, the prime minister—who should have been held accountable after the September events—has instead moved to consolidate control within his party by sidelining emerging younger leadership. These are not isolated leadership failures; they are predictable outcomes of a system in which internal party democracy was never meaningfully enforced.

In the absence of a credible referee, Nepal’s political arena increasingly resembles a soccer match without one—rules exist on paper, but no one is willing, or empowered, to enforce them.

The Election Commission’s failure—or unwillingness—to implement an electronic voting system for the millions of Nepali citizens in the diaspora, who dutifully pay taxes back home and help keep the national economy afloat through their work abroad, is another telling example of why the institution requires serious reform.

When the System Turned on Itself

A vast majority of youths, particularly Gen-Z, began to see the system for what it was: murky, exclusionary, and brittle—like a house of cards.

September 8 marked a tragic turning point, when innocent youths were killed by a coalition government unable—or unwilling—to read the moment. What followed on September 9—the widespread destruction across the country—may not have been centrally orchestrated. It looked more like political tribes turning on one another, the inevitable outcome of three decades of cadre-based fragmentation. Ongoing investigations will, of course, uncover much-needed truth behind these events.

The anecdote shared by Gagan Thapa—of his house being attacked by a high-level member of a major party close to its leadership—is illustrative. When politics becomes tribalized all the way down, violence no longer requires ideology; it only needs identity. There are many other such examples.

The reflex response has been predictable. Analysts rushed to blame foreign hands and shadowy conspiracies. But a more honest starting point lies closer to home. A hard self-reflection on party machinery—their incentives, operations, militant culture, and internal pathologies—offers far more explanatory power than external scapegoats. In any case, rushing to preconceived judgments is premature.

The Missed Constitutional Gatekeeper

So where do we go from here?

Nepal does not lack capable professionals, credible leaders, or socially aware citizens. What it lacks is access. The old guard has functioned as a gatekeeper, blocking entry into meaningful political leadership.

One institution was constitutionally empowered to prevent this capture—and failed.

That institution is the Election Commission.

As I have repeatedly argued that the Article 269 of the Constitution provides clear democratic rules for political parties. Yet the recent candidacy debacle makes clear that the Election Commission has repeatedly shirked its duty to enforce those rules. For example, the seven-day concession for candidacy list “refinement” was not reform; it was an admission of institutional retreat. Their silence on the NC party’s constitutional provision about the legitimacy of the special convention only adds fuel to the fire.

Simply put, for years, the Commission failed to help map Nepal’s democratic middle corridor.

What a Democratic Reset Actually Requires

This moment calls for seriousness, not symbolism.

Politics is less about good actors versus bad actors than about the limits institutions set. Behavior is shaped and tested by those limits. Just look at how even new political hopefuls quickly suspend their stated ethos when operating under weak oversight and loose rules. Ethics are only as strong as the guardrails they operate within.

Nepal’s democracy does not need another ritual performed on paper. It needs institutional discipline restored—so that parties once again compete for public trust rather than capture the state.

Nepal’s Red Queen does not need celebration. It needs restraint.

That restraint can only come from institutions willing to enforce the rules already written into the constitution and shackle the party leviathan. Only then can Nepal move from paper democracy toward liberal democracy—back onto the middle corridor where state and society can once again run, not collapse, together.

Dr. Alok K. Bohara, Emeritus Professor of Economics at the University of New Mexico, writes as an independent observer of Nepal’s democratic evolution through the lens of complexity and emergence science. His systems-policy essays on Nepal’s socio-economic and political landscape appear on Nepal Unplugged.