They used to say love is blind. Yes, it was — but that was before it had its vision corrected by Dr. Suman Thapa at Ek Ek Paila. Love now not only sees clearly — it also evaluates land titles, car models, and visa prospects before daring to fall again.

Once upon a time, love blossomed quietly in Ratna Park, nourished by titaura and pustakari, whispered behind college notebooks, and carried through blue aerogram letters. Today, it thrives on Instagram reels, filtered through ring lights, and powered by eSewa. What was once innocence has now become a strategic investment. From a sociological standpoint, we find ourselves in the era of rationalized romance. Max Weber might call it the bureaucratization of affection; Marx would call it the commodification of intimacy. Where love once required only courage and heart, today it demands spreadsheets and social validation. Kathmandu’s youth joke, half-seriously, maya pani aba market ma chha — love too is for sale.

Modern love no longer falls — it calculates. The formula is simple:

Love = Salary × (House + Car × Visa Prospects).

Even Cupid has gone corporate. He no longer carries arrows; he carries spreadsheets titled “Feasibility of Long-Term Commitment.” Hearts are audited quarterly; breakups are treated as fiscal losses. The girl asks, “Do you own land in Bhaktapur or just dreams in Baneshwor?” The boy replies, “You’re a stable emotional asset with low volatility and high return.” Our parents had arranged marriages; we have algorithmic ones. Bhaat khayeko kura has been replaced by bio padheko kura. The dowry system didn’t vanish; it rebranded — now hidden in degrees, dual passports, and deferred American dreams. Even Nepali love songs have evolved: where lyrics once declared “Maya ta maya ho,” they now whisper “Maya ta EMI ho.” Affection comes in monthly installments; heartbreaks renew automatically, like Netflix subscriptions.

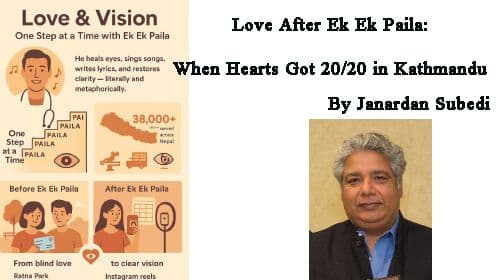

Dr. Suman Thapa and Ek Ek Paila: Healing Sight, Restoring Hearts

Before we criticize love for its LASIK, credit must go to Dr. Suman Thapa, the man behind the surgery. Just as LASIK corrects vision, Dr. Thapa’s work at Ek Ek Paila has “corrected” the way we see and experience love in Kathmandu.

Dr. Thapa is no billboard celebrity. He is a world-class ophthalmologist, holding both an MD and a PhD, globally educated yet deeply rooted in Nepal. In a city obsessed with titles and image, he remains grounded, letting his work speak louder than words.

When the 2015 earthquake struck, Dr. Thapa didn’t flee abroad. Instead, he and his best friends collectively founded Ek Ek Paila, an organic, Nepali-grown initiative born out of urgency and compassion. Its name means “One Step at a Time,” and that’s exactly how it has changed lives: through mobile eye camps, rural cataract surgeries, and free outreach programs—quiet miracles restoring both literal and symbolic sight.

He is truly a well-rounded figure: healer, pioneer, and unintentionally, a heartthrob. His soft-spoken voice, professional respect, and gentle charm make him captivating among women of all ages—unmarried, married, or older adults. Many attend his concerts not for pop culture but for the music itself, performed by his band. Yes, Dr. Thapa has a deep love for music. At each concert, women outnumber men, and the men—boyfriends, husbands, or friends—support them: keeping glasses filled while the women swoon over the lead vocalist. His voice—warm, commanding, and slightly mischievous—fills the room with laughter, admiration, and playful vows of unrequited love.

He is a vegetarian who prefers Padamchaal, the local millet-based brew from Jiri, over imported single malts. He drinks tradition, not status. Educated globally, rooted locally, humble personally, and socially charismatic, he embodies a paradox: the perfect healer for the modern Nepali heart—precise, ethical, and deeply human. His paradoxical nature keeps us engaged and curious.

Who better than Dr. Thapa to cure love’s blindness? After all, he dedicates his life to restoring vision but somehow maintains clarity in human affection, ethics, and melodies. Under his care, love undergoes a successful fix—no anesthesia needed, only awareness and perspective. His work offers hope for a future where love can see clearly again.

When the bandages come off, love blinks and finally perceives the world as it truly is. It realizes it’s no longer in Ratna Park—it now sits in boutique cafés where an Americano costs more than a day’s wage in Jiri. It notices couples taking selfies in electric cars financed by parental savings, hashtags proclaiming “#soulmate” followed by “#sponsorship.” It perceives the new geography of desire— from rooftops and moonlit terraces to Airbnb apartments and visa lines.

The New Economics of the Heart

Love recognizes it has been privatized; emotions have become commodities accessible only to those with disposable income and social capital. This shift reflects Kathmandu’s changing socio-economic landscape—shaped by remittance, migration, and aspiration. Nepali romance today is a curious mixture: partly digital modernity, partly feudal nostalgia. Once, couples shared secrets and pustakari; now they share passwords and Netflix accounts. Emotional give-and-take has been replaced by digital visibility—you’re truly loved only if your partner posts your picture with a heart emoji.

Even heartbreaks have gone global—the same youth who once cried under Dharahara now post heartbreak reels from Dallas or Dubai. Migration has made love long-distance; capitalism has made it high-maintenance. Sociology has never been more dramatic.

Dating apps treat people like commodities; partners are judged through social, economic, and cultural filters. Young women are labeled “materialistic,” yet they act rationally in a system that values stability as survival. Young men complain that love has become expensive, even as they approach it like venture capitalists pitching startups. Families accept it: “He’s from America,” they say, as if geography alone makes someone virtuous. Love has become Nepal’s export—alongside remittance, labor, and emotion. The new dowry is a Western Union receipt.

From Bourdieu’s perspective, social capital has replaced spontaneity. Likes, follows, and curated photos now serve as currency; attending the “right” wedding matters as much as love itself. Emotional exchanges have turned bureaucratic.

Yet, amid all this irony, human longing persists. Beneath our economic pragmatism, the heart still searches for that brief titaura moment when eyes meet and everything else fades. Perhaps love’s blindness was never a flaw—perhaps it was innocence, the ability to see without judging worth. Maybe we didn’t need to fix love’s vision at all; possibly we needed to fix ourselves.

Still, if love needed to regain sight, it was lucky to have chosen Dr. Suman Thapa at Ek Ek Paila—a man who heals quietly, drinks Padamchaal, sings beautifully, and inspires admiration without self-promotion. So yes, love was blind once. But after seeing Kathmandu’s rent prices, tuition fees, and inflated American dreams, it decided to open its eyes—under the steady, ethical hands of Dr. Thapa.

And that, perhaps, is the most Nepali ending possible: even love, to survive here, occasionally needs an eye doctor. Yet for the truly stubborn—those who claim modern lovers have burned the Singha Durbar, Supreme Court, or Parliament—know this: the blindness is yours, not love’s. In that case, dear reader, you are beyond Ek Ek Paila’s repair. Go to Tilganga, or perhaps somewhere even more radical, for Dr. Thapa’s vision, ethics, and melody can cure much—but not willful blindness.

(Dr. Janardan Subedi is Professor of Sociology at Miami University, Ohio. He writes on political ethics, democratic transitions, and institutional accountability in South Asia.)

@HT